3 Film Financing Myths, Hacked by Data

文章转载自:UniFi影视完片担保

The knives are out once more for the film business. A week into April and we’ve already had our fill of damning news stories. A Wall Street Journalinvestigation exposed the convoluted money trail behind Martin Scorsese’s “Wolf Of Wall Street;” days later, leaked files from a Panama-based law firm pointed the finger at several big film names as being among those reputed to have squirreled money away in offshore companies; and now comes intimations that yet another Hollywood studio, Warner Bros, is retrenching in favor of fewer, more branded franchise films after a run of lackluster returns from more ambitious, filmmaker-driven projects.

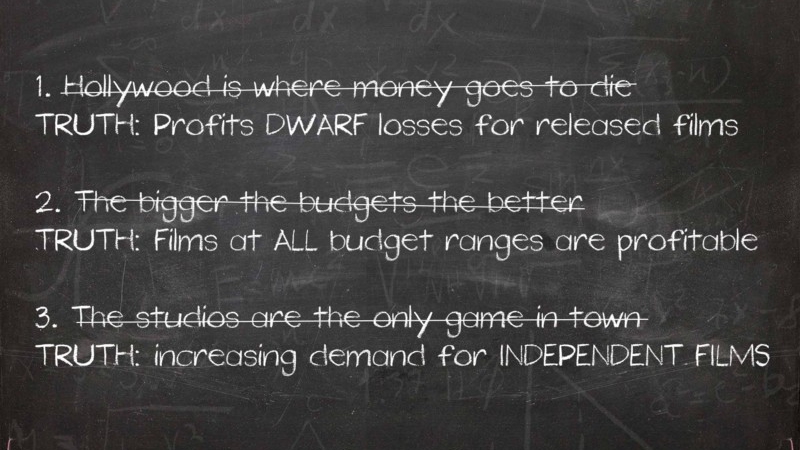

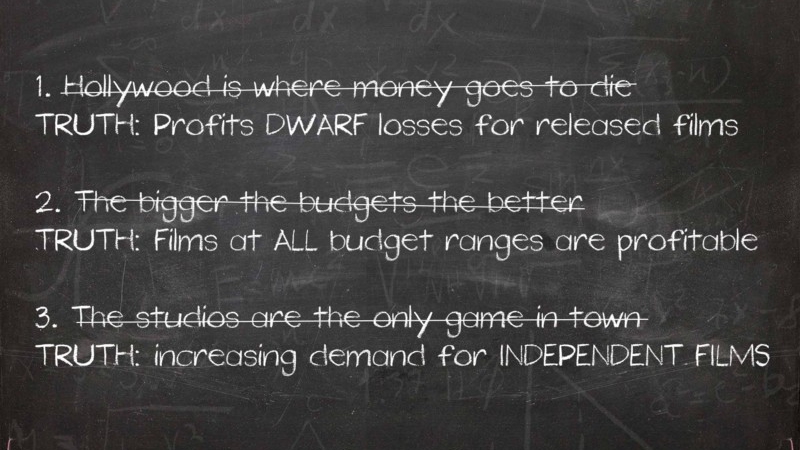

The knives are out once more for the film business. A week into April and we’ve already had our fill of damning news stories. A Wall Street Journalinvestigation exposed the convoluted money trail behind Martin Scorsese’s “Wolf Of Wall Street;” days later, leaked files from a Panama-based law firm pointed the finger at several big film names as being among those reputed to have squirreled money away in offshore companies; and now comes intimations that yet another Hollywood studio, Warner Bros, is retrenching in favor of fewer, more branded franchise films after a run of lackluster returns from more ambitious, filmmaker-driven projects.Read all this and cinema comes across as a financial sinkhole that operates behind impenetrable walls of secrecy and corporate layers of risk aversion. A cesspool fit only for billionaire fools and studio bookkeepers. It’s a typecast stereotype, however. The boring reality is that Hollywood has fallen prey once more to its own myth-making prowess. Its celebrity machine feeds on the salacious. If you look at the underlying data, as the analytics team atSlated has just done, what you will actually find is a routinely profitable business that flies in the face of so many popular misconceptions, many of them perpetuated by cinema itself. Let’s examine the biggest myth of all.

Far from being that treacherous money-pit of common mythology, Hollywood aggregates tens of billions in global profits every year. No wonder China wants in: The overall return on investment rivals that of Silicon Valley. (And no wonder too, perhaps, the urge to shelter some of those impressive returns in tax-friendly havens.)

Counter-intuitive as these numbers might seem given all talk of disrupted business models and audience fragmentation, they are based on publicly available figures. Slated summoned them up as part of an internal exercise to test its own scoring system against real world “ROI” results. Slated looked at all movies released theatrically on at least one screen in North America between January 2010 and October 2015. There were more than 2800 films in that dataset, for which it had reliable production budget numbers for 1609.

To determine ROI, the following formula was used: (worldwide gross box office revenue) minus (estimated marketing costs, as a percentage of production budget) plus (estimated tax credits/soft money) divided by (production budget). Gross theatrical revenue was used rather than theatrical rentals primarily because reliable numbers for worldwide TV and video revenue are not publicly available for this dataset, but also because worldwide gross box office numbers have historically been a decent proxy for adjusted gross revenue from all sources.

This is an admittedly crude yardstick for measuring ROI, but it offers a truer big picture than all the minutiae of a studio spreadsheet. We are not trying to adjudicate the complexities of profit participation here in an attempt to determine the various beneficiaries — or not — of those investment returns. This is not about the deal terms that investors, studios, distributors, producers and everyone else along the value chain are able to negotiate for themselves. We’re simply asking ourselves whether the cinema’s box office winners outweigh the losers and, if so, where do the sweet spots lie. As it happens, the answer to that last question may surprise you as well.

The widely held assumption is that the studios have turned their headlamps onto the big-budget blockbusters because that is where the outsize profits are to be made.With such huge overheads to cover, it doesn’t make obvious sense to expend all that costly executive time on smaller films that may end up requiring even more marketing ingenuity to find their audience than comic-book stories.But one look at Slated’s ROI by Budget Size chart and you question the wisdom of this mega-budget obsession. When it comes to theatrical releases, it turns out that all budget sizes have shown overall profits.

The tent poles show positive returns, for sure, but the good news for smaller studios unable to bet the farm on such extravaganzas is that there are so many other fruitful budget brackets to pick from. Films costing $20m, even $50m, are very profitable too and won’t bring down the house of cards if several fail at once. For the rest of us, operating in the independent realm, you’ll be happy to know that the $5 million-and-under tadpoles almost match the investment returns of their supersized predators at the box office.

We are not the only ones revisiting some of Hollywood’s core tenets. In his revealing profile of STX Entertainment, The New Yorker writer Tad Friend noted in January that the blockbuster game is a fantastic business to be in when it works, which is why conglomerates keep buying studios. But, as Warner Bros may now be learning with “Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice”, it’s getting steadily less fantastic. Which is why conglomerates keep selling those studios. As one studio head told the author: “The hundred-million-dollar Roland Emmerich movie that does five hundred million worldwide — every year, our profit on it goes down.” Already, we are seeing the danger signs. Last year, more than 25% of total box office revenues — as opposed to profits — came from just five films. The endgame, as Cowen & Company analyst Doug Creutz warned recently, may be more far-reaching than just a marketplace condensing into fewer, but bigger hits. When the videogame industry faced a similar dilemma, several of its biggest players crashed and went out of business.

Any studio contraction would be a continuation of a decade-long trend. As you can see from our third chart, the Hollywood studios have been pulling back steadily on the number of annual releases ever since 2006, the height of Hollywood’s hedge fund binge. In their place has come an increasing volume of lower-budget films financed and distributed outside the studio system, all competing to fill the demand vacuum.

That demand is fueled as much by the theatre chains and their audience needs, as it is by the collective appetite of all digital distribution outlets such as Netflix and Amazon that have mushroomed. STX had no discernible track-record of making movies and yet AMC Theaters, now the largest chain in the US, committed to exhibiting its future pipeline because of that very demand. As AMC’s chief explained to Tad Friend:

“We need more movies. The studios are in the sixteen-week-a-year business, so they worry about sixteen Fridays. I worry about fifty-two Fridays. And STX will bring back a broader audience for the brainier, more intricate movies — not just the twenty-one-year-old who’s there for the explosions.”

As it happens, STX based much of its business plan around a key data-point stumbled across when deciphering ten years worth of box office performance figures. STX’s research showed that star-showcase films, within a budget range of $20m-$80m, were profitable thirty per cent more often than the average Hollywood film. Emboldened by this insight, and considerable Chinese backing, STX has plans to make as many as twelve to fifteen such movies a year.

Other would-be studios are also applying this “Moneyball” approach to filmmaking, including Legendary Entertainment which has turned to an applied analytics team from the world of sports in a bid to improve the cost-efficiency of its marketing campaigns. They know that film is an inherently stable business provided you confront the risks objectively, dispassionately and with an understanding of what statistics brings to the equation. As Legendary’s data scientist Matt Marolda explains:

“Analytics never created a great athlete. But they can help a manager put him in the best position to succeed. It’s the same with entertainment content. You want to put it in the best position to succeed. We’re just trying to increase our odds and be smarter.”

At Slated, we believe it’s high time that independent filmmakers, together with investing support systems, take advantage of the same methodical thinking. Data-driven analysis may not appeal to our romantic notions of filmmaking as a defiantly quixotic adventure. We like our movies to be dangerously unpredictable — but that doesn’t mean the business surrounding those movies needs to be too.

This blog post is the first in a new filmonomics @ slated series that will look at film financing and project packaging through the lens of statistical analysis. We will use hard numbers and our own scoring algorithms to re-examine some of the foundational thinking behind the movie business. Next up as topics:

- The Smarter Way t0 Hit the Film Financing Bullseye

- Using Science To Pick Hit Movies